Author(s):

Ahmad A Mousa*

Monash University – School of Engineering, Malaysia

Received: 06 July, 2015; Accepted: 08 September, 2015; Published: 10 September, 2015

Ahmad A Mousa, Senior Lecturer, Monash University – School of Engineering. Malaysia, E-mail:

Mousa AA (2015) Six Sigma DMAIC for Shaking Stagnant Construction Cultures – A Conceptual Perspective. J Civ Eng Environ Sci 1(1): 013-020. 10.17352/2455-2976.000004

© 2015 Mousa AA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Cultural barrier is always perceived as the prime challenge for modernizing idle construction markets. Unsurprisingly, most changes in construction hinge on understanding the benefits of sustainable transformation. Persistent attempts in stagnant construction cultures have materialized in some noted changes. Successful sustainable transformation in such economies appears to be chiefly impeded at the execution level. The Kotter's model for change is globally accepted approach for comprehensive implementation of major business transformations. Modern organizational change initiatives typically embrace the notions of Six Sigma in a broader sense. This concept paper propose the use of Six Sigma DMAIC technique for reforming stagnant construction cultures. A case study from a challenged construction market is referred to for potential implication.

Introduction

Sustainable construction is a comprehensive process pillared on adopting the principles of sustainable development over the entire construction cycle [1]. As such, all costs – direct and indirect – should be considered for objective comparisons between construction alternatives. Sustainable gains of non-monetary nature over the life cycle of a structure or project need to color business decisions. Globalization has driven the need for sustainable transformation in numerous idle construction markets. Economies in these markets are socially, technologically and often politically challenged beyond traditional and gradual local solutions for reform. Mousa [2] has analyzed common barriers impeding sustainable construction development in challenged economies using aggregated STEP analysis. He also scrutinized the mechanics of idle construction markets for a more rigorous business mitigation of the root causes. Mousa [2] has also proposed the use of Kotter's model for a paradigm sustainable change in these economies. The change process should endure the three stages of the model: unfreeze-change-lock. The Egyptian concrete market was referred to as an example of unprivileged construction cultures. It is the author's opinion, however, that pertinent literature demonstrated a disproportionate emphasis on management and business dimensions for sustainable construction transformation. In this study the use of Kotter' model for change combined with Six Sigma DMAIC is advocated as an efficient management tool to carry out the desired sustainable construction transformation in stagnant cultures. The study provides practitioners with a perspective for potential business resolutions at the conceptual level. It is hoped that this proposal is further evaluated and implemented in local contexts. Some level of market-dependent treatment is apparently needed.

Characteristics of a Stagnant Construction Culture

Numerous studies have closely investigated sustainable transformation of construction markets particularly in emerging and challenged economies. This interest is fueled by the burgeoning global concerns and challenges on several fronts: energy, environment and natural resources. The following summarizes the nature and mechanics of stagnant construction cultures, barriers to sustainable transformation, and past attempts to tackle the problem.

Nature and mechanics of the problem

Stagnant construction cultures intuitively oppose sustainable transformation attempts in most any form: products, practices, and regulations. The majority of developing countries have idle construction markets - globally perceived unattractive except for mega projects. Numerous literature have repeatedly highlighted the unsustainable characteristics of such markets. In a broader sense, these construction practices includes dated building codes and specification, weak enforcement of construction regulations, absence or scarcity of sustainable solution, lack of awareness of energy and environmental concerns, limited understanding of durability and life cycle concepts, market monopoly and absence of healthy competition [2,3]. These economies are apparently unappealing to sustainable materials due to the low intensity of competition with traditional (existing) materials. The concept of competitive strategy is described as the search for a favorable competitive position in an industry [4]. In any industry there are five forces that are likely to determine the nature and structure of competition: threat of new entrants, threat of substitutes, bargaining power of customers (buyers), bargaining power of suppliers and the rivalry among the existing competitors [5]. The dominant presence of unsustainable/traditional practices in stagnant cultures poses a market threat to introducing sustainable solutions. In such economies, prime market stakeholders are unaware of the superiority of sustainable gains and, hence, oppose change. The overwhelming power of “old-school” customers and suppliers impedes the bargaining power of new market entrants (sustainable solutions). Driven by the low market demand, investors in new construction solutions become unmotivated to take any risk. This value-deficient environment creates uncompetitive (stagnant) market with stakeholders unable to recognize the benefits of a healthy competition on the long term [6]. These evident mechanics of stagnant construction markets limit global competitiveness and universal business attraction.

Common market barriers

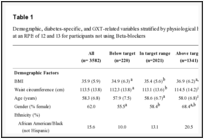

The concept of replacing a well-established material with a more sustainable substitute – perceived as a rival –intuitively faces resistance in any construction market. Pertinent literature has diagnostically highlighted local barriers with recommendations to promote sustainable construction practices [7-10]. More generically, Du Plessis [1] investigated these barriers in developing countries. Typical sustainability barriers in challenged economies are grouped in four categories: political, economic, sociocultural and technological (Table 1). This grouping allow investigating these barriers using PEST analysis [2]. From a business standpoint, studying the culture and readiness of construction markets for sustainable transformation gives better insight into identification of the impediments and resolutions.

Attempts for transformation

The concept of replacing a well-established material with a more sustainable substitute – perceived as a rival –intuitively faces resistance in any construction market. Pertinent literature has diagnostically highlighted local barriers with recommendations to promote sustainable construction practices [7-10]. More generically, Du Plessis [1] investigated these barriers in developing countries. Typical sustainability barriers in challenged economies are grouped in four categories: political, economic, sociocultural and technological (Table 1). This grouping allow investigating these barriers using PEST analysis [2]. From a business standpoint, studying the culture and readiness of construction markets for sustainable transformation gives better insight into identification of the impediments and resolutions.

Attempts for transformation

Numerous studies have closely investigated the modest presence of sustainable construction materials and practices in stagnant cultures. The multidimensional nature of sustainable transformation has been investigated with emphasis on one or more of the following: materials, structural design, architectural design, energy, environment, policies, management, strategic planning, life cycle, durability, and economy. In doing so, the adopted approaches utilized surveys, value engineering, and risk management, identification of sustainability barriers, and rating level of understanding, comparative analysis, policy reviews, case studies, and strategic frameworks (Table 2). Some studies employ more than one of these tools.

-

Table 2:

Summary of selected literature on sustainable construction transformation in challenged markets.

Table 1:

Typical sustainability barriers in stagnant construction cultures.