Authors:

Nadia Garnefski1*, Samiul Hossain2,3 and Vivian Kraaij4

1Associate Professor at Leiden University, the Netherlands, Department of Clinical Psychology, Netherlands

2Lecturer and clinical psychologist at North South University, Dhaka, Bangladesh, School of Health & Life Sciences, Department of Public Health, Bangladesh

3PhD candidate, Centre for Emotional Health, Macquarie University, Australia

4Associate Professor at Leiden University, the Netherlands, Department of Clinical Psychology, Netherlands

Received: 01 June, 2017; Accepted: 03 July, 2017; Published: 05 July, 2017

Nadia Garnefski, Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Leiden, P.O. Box 9555, 2300 RB Leiden, Netherlands, Tel: +31715273774; E-mail:

Garnefski N, Hossain S, Kraaij V (2017) Relationships between maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and psychopathology in adolescents from Bangladesh. Arch Depress Anxiety 3(2): 023-029. DOI: 10.17352/2455-5460.000019

© 2017 Garnefski N, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Emotion-regulation; Coping; CERQ; Adolescents; Psychopathology; Mental health

Introduction: Psychopathology of adolescents in developing countries such as Bangladesh is a neglected problem, which should get more attention, especially with a focus on finding targets for prevention and intervention. Aim of the study was to study relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and psychopathology in Bengali adolescents.

Methods: The sample consisted of 340 12-to-18-year old adolescents from Bangladesh. The Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) was used to measure cognitive emotion regulation strategies. The SCL-90 was used to measure symptoms of depression, anxiety and hostility. Relationships between CERQ and SCL-90 scales were studied by Multiple Regression Analysis.

Results: With regard to relationships between CERQ strategies and psychopathology: Higher extents of ‘Worry-focused’ cognitive styles appeared to be related to the reporting of more symptoms of psychopathology, while more ‘Reappraisal-focused’ styles were associated with the reporting of less symptoms of psychopathology.

Discussion:The results with regard to the relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and psychopathology may provide possible targets for interventions to improve mental health in adolescents in developing countries.

Introduction

Research on psychopathology in developing countries is still very scarce. Still, it is widely acknowledged, that mental disorders constitute an important and neglected problem in these countries, putting a high and often life-long burden on people living with it [1]. Only a limited number of studies were performed with regard to the prevalence of mental health disorders in Bangladesh, which were summarized in a recent review by [2]. The results showed that prevalence rates of mental disorders (most commonly depression and anxiety) varied from 6.5 to 31% in adults and from 13.4 to 22.9% in children and adolescents [2]. Underreporting and under-diagnosis, however, were assumed with regard to these figures, because of the strong stigma associated with mental disorders in this country. Nevertheless, the data suggest that mental disorders constitute a major issue that should get attention, especially with a focus on finding targets for prevention and intervention.

In countries with more advanced economies, it has repeatedly been shown that the development and maintenance of psychopathology might be associated with poor cognitive emotion regulation. In addition, it has been shown that changing people’s cognitive emotion regulation strategies could be an important target for prevention and treatment [3]. The present study will focus on these issues in adolescents in a developing country, i.e. Bangladesh. Before carrying on to the specific aims of the study, first the concept of cognitive emotion regulation and the associated Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) will be explained.

Cognitive emotion regulation refers to the mental strategies that people use to deal with traumatic or stressful events [3-5]. It can be considered a part of the broader concept of emotion regulation which can be defined as ‘extrinsic and intrinsic processes responsible for monitoring, evaluating and modifying emotional reactions, especially their intensive and temporal features’ [6]. Although the handling of stressful events is important in all stages of life, adolescence is the period in which cognitive emotion regulation skills are acquired. It has repeatedly been suggested that the cognitive strategies that adolescents use to manage their stressors might be related to the development of psychopathological problems [7]. Therefore, insight into the specific cognitive emotion regulation strategies that adolescents use, and into the way that they are associated with maladjustment, might give important information for prevention and intervention of psychopathology in this age group.

In 2001 the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) was developed [4]. The CERQ is a self-report questionnaire assessing which specific cognitive emotion regulation strategies people use to handle threatening or stressful events. Nine cognitive emotion regulation strategies are distinguished by the CERQ on theoretical and empirical bases, each referring to people’s cognitions or thoughts after they have experienced threatening or stressful events [4], was the first paper in which the nine strategies were described: ‘Self-blame, referring to thoughts of putting the blame of what you have experienced on yourself; Other-blame, referring to thoughts of putting the blame of what you have experienced on the environment or another person; Rumination or focus on thought, referring to thinking about the feelings and thoughts associated with the negative event; Catastrophizing, referring to thoughts of explicitly emphasizing the terror of what you have experienced; Putting into Perspective, referring to thoughts of brushing aside the seriousness of the event / emphasizing the relativity when comparing it to other events; Positive Refocusing, referring to thinking about joyful and pleasant issues instead of thinking about the actual event; Positive Reappraisal, referring to thoughts of creating a positive meaning to the event in terms of personal growth; Acceptance, referring to thoughts of accepting what you have experienced and resigning yourself to what has happened and Refocus on Planning, referring to thinking about what steps to take and how to handle the negative event’.

Since its development, the CERQ has been translated into several languages. These languages include among others: Dutch [8], English [4], Spanish [9], Italian [10], Turkish [11,12], Persian [13,14], Chinese [15], French [16], German [17], Hungarian [18] and Romanian [19]. One consistent finding across these studies is that good psychometric properties are observed for the instrument. A second consistent finding across countries is that, generally speaking, more psychopathology is observed in people using specific maladaptive cognitive strategies like self-blame, rumination, and catastrophizing, while less psychopathology is observed in people using specific adaptive strategies like positive re-appraisal or positive refocusing. An important conclusion from cognitive emotion regulation research is therefore that interventions should teach people to replace maladaptive strategies like rumination or catastrophizing by more adaptive strategies like positive reappraisal.

Until now, we do not know anything about the use of cognitive emotion regulation strategies and their associations with psychopathology in a developing country like Bangladesh. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to study relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and psychopathology in Bengali adolescents. With this research, we hope to find targets for psychological interventions for youngsters with psychopathology in developing countries like Bangladesh. We expect that although adolescents from developing countries may differ in the reporting of certain strategies from other countries, the type of the relationships between specific cognitive emotion regulation strategies and psychopathology remains the same as in other countries. Before performing analyses to answer the main question, factor structure and psychometric properties of the Bengali version of the CERQ were investigated.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 340 12-to-18-year old adolescents (mean age 14 years and 4 months; SD=1.59), attending a secondary or higher secondary private school in Dhaka (Bangladesh). According to the educational system in Bangladesh, higher secondary school refers to pre-university level, whereas secondary school can be described as intermediate to higher vocational education. The sample consisted of 272 females (80.0%) and 330 pupils (97.1%) had an Islamic religious background (97.1%).

Procedure

The study was performed at two secondary schools and one higher secondary school in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. Initially, four schools had been approached for participation, by writing them an invitation letter. They were selected by convenience sampling. One of them did not respond to the invitation. Students completed a written questionnaire during school hours. They were supervised by a teacher and a post-graduate psychologist. The students were guaranteed anonymity in relation to their parents, teachers, and fellow students. Prior to data collection, a written informed consent was obtained from the participants. In addition, oral consent from the parent or guardian was obtained. Three participants withdrew from the study. The study was conducted under the responsibility and supervision of researchers from Leiden University, The Netherlands.

The study procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology, Leiden University and conform to the provisions of the declaration of Helsinki.

Instruments

Cognitive emotion regulation strategies: Cognitive emotion regulation strategies were measured by the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) [4], translated into Bengali by using the translation-back-translation method. The CERQ is a self-report questionnaire assessing what people think after the experience of threatening or stressful events. The CERQ consists of 36 items and has nine conceptually different subscales: Self-blame, Other-blame, Rumination, Catastrophizing, Putting into perspective, Positive refocusing, Positive reappraisal, Acceptance, and Planning. Each subscale consists of 4 items. Answer categories range from 1 (never) to 5 (always). A subscale score can be obtained by adding up the four items (range: from 4 to 20), indicating the extent to which a certain cognitive emotion regulation strategy is used. It has been shown that the alpha-reliabilities of the subscales range from .68 to .83, with five of the alpha’s higher than .80 [3,4].

Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety, and Hostility: Symptoms of Depression, Anxiety, and Hostility were measured by three subscales of the SCL-90 [20], translated into Bengali by using the translation-back-translation method. The Depression subscale consists of 15 items, referring to the extent to which the participants report symptoms of depression (one of the original 16 items was dropped; this was the item concerning loss of sexual interest; it was dropped because of the age of the subjects). The Anxiety subscale consists of 10 items, referring to the extent to which participants report symptoms of anxiety. The Hostility scale consists of 6 items, referring to the extent to which participants report symptoms of hostility. Answer categories of the items range from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). Scale scores are obtained by summing the items belonging to the scale. Previous studies have reported good psychometric properties and strong convergent validity with other conceptually related scales [20].

Data analysis

First the factor structure of the CERQ-Bengali was analysed by Factor Analysis. Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities of all scales were calculated. Means and standard deviations of all scales were provided. Bivariate relations among CERQ scales and Depression, Anxiety, and Hostility scales were analysed by Pearson correlations. Multivariate relationships between CERQ scales and Depression, Anxiety, and Hostility scales were analysed by Multiple Regression Analysis (method: stepwise).

A power analysis was performed to determine the sample size needed. Based on a medium large effect size (f) of 0.40, a two-sided alpha of .05 and a power of .80, a minimum of 115 adolescents with completed questionnaires are needed in order to perform a Multiple Linear Regression Analysis with nine predictors. Taking into account the possibility that 10% might not complete the questionnaire after they were approached, it was determined that at least 130 adolescents had to be included in the study. However, the aim was to include even more adolescents, to increase the power. We eventually succeeded in including 340 adolescents.

Results

Factor structure of the CERQ-Bengali

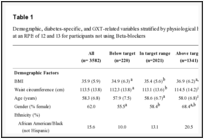

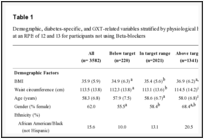

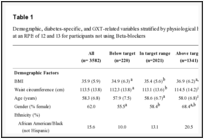

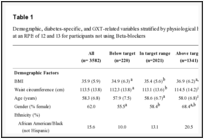

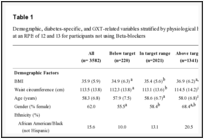

Factor Analysis was performed on the CERQ items by Principal Axis Factoring with Varimax rotation. Three factors were extracted, on basis of the eigenvalue > 1 criterion, with a total variance explained of 38.5%1. Communalities of the variables were all .20 and higher, except 3 of the 4 Other-blame items, which had communalities of .10 and lower. Because the Other-blame scale had a non-acceptable Cronbach’s alpha reliability (next paragraph), it was decided to omit the items of this scale from the analysis. In the new factor analysis again three factors were extracted, with a total variance explained of 39.4%. The results are presented in Table 1.

The first factor reflected the four ‘Reappraisal-focused’ strategies: Positive refocusing, refocus on Planning, Positive reappraisal, and Putting into Perspective. Factor loadings of the variables of these scales ranged from .34 to .71. None of the items had high(er) loadings on another factor. The second factor reflected the three ‘Worry-focused’ strategies: Self-blame, Rumination, and Catastrophizing. The majority of items ranged from .38 to .71. Only one of the Catastrophizing items (item 35) loaded higher on the first ‘more adaptive’ factor, with a factor loading of .60, than on its own factor (.29). This finding will be further explored in the reliability analyses. The third factor was more difficult to interpret. Two items of the acceptance scale loaded high on this factor (.73 and .57), but the other two items (20 and 29) did not. Also this finding will be further explored in the reliability analysis.

__________________________________

1Also Factor analyses with other number of factors were performed, among which an eight and nine factor solution. In all analyses the same three main factors showed up. The three factor solution therefore not only fulfilled the scree criterion, but also was the best interpretable solution. The original nine factor solution from Garnefski et al (2001) could not be confirmed by confirmatory factor analysis.

Reliabilities, means and standard deviations

First, Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities were computed for the nine original CERQ subscales (Table 2). In correspondence with the factor analysis results, the reliability of the scale Other-blame was unacceptably low. Therefore, this scale was omitted from further analyses. Reliabilities of the other eight scales ranged from acceptable (.62; Acceptance) to good (.77; Rumination, Planning), which could be considered satisfactory, considering the number of items per scale (4). For all but one scale deleting items did not lead to improvement of the alpha reliability. Only for the Acceptance scale, deleting two items lead to the improved alpha of .72. Because also in the factor analysis these two items did not have their highest loading on the same factor as the other two items, it was decided to work further with the two-item scale for Acceptance. With regard to Catastrophizing (showing mixed findings in the Factor Analysis), no further improvements could be made by removing items. Therefore, it was decided to keep the four items of this scale.

-

Table 2:

Reliabilities of the CERQ scales

In addition to the original CERQ subscales, two composite scales were constructed, corresponding with the Factor Analysis results. The first composite scale included the items of the four subscales that had high loadings on the first factor: Positive refocusing, refocus on Planning, Positive reappraisal, and Putting into Perspective. This scale was called the ‘Total Reappraisal-focused’ emotion regulation scale. The second composite scale included the items of the four subscales that had high loadings on the second factor of the Factor Analysis: Self-blame, Rumination, and Catastrophizing. This scale was called the ‘Total Worry-focused’ emotion regulation scale. High reliabilities were found for both the ‘Total Reappraisal-focused’ (.90) and the ‘Total Worry-focused’ (.87) composite scales.

With regard to the SCL-90 Depression, Anxiety, and Hostility scales, Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities were .80, .86, and .69, respectively.

Means and standard deviations of all scales are provided in table 3, including number of items, possible and actual range of the scale scores. The cognitive emotion regulation strategy that was reported most often was Refocus on planning and the cognitive emotion regulation strategy that was reported least often was Self-blame.

-

Table 3:

Means and Standard deviations.

Pearson correlations

Pearson correlations among original CERQ subscales ranged between .31 (Acceptance and Positive refocusing) and .73 (Refocus on Planning and Positive Reappraisal) with a mean Pearson correlation coefficient of .52 (Table 4). This indicates moderate to strong correlations among the subscales (Table 2). Pearson correlation between the two composite scales was .65. In addition, correlations between CERQ scales and depression, Anxiety, and Hostility scales are presented in table 4.

-

Table 4:

Pearson correlations among CERQ scales and between CERQ scales and Depression, Anxiety, and Hostility scales.

Multiple regression analysis with separate CERQ scales as ‘predictors’

To study the extent to which symptoms of depression, anxiety, and hostility were predicted by the separate cognitive emotion regulation strategies, Multiple Regression Analyses (Method: stepwise) was performed with depression, anxiety, and hostility as dependent variables and the eight separate CERQ subscales as independent variables (Table 5).

-

Table 5:

Multiple regression analysis (stepwise) subscales.

All three regression models were significant (p <0.001). Percentages of explained variance were 45% for the prediction of Depression scores, 37% for the prediction of Anxiety scores, and 19% for the prediction of Hostility. With regard to Depression, significant positive ‘predictors’ were Rumination, Self-blame, and Catastrophizing, and a significant negative ‘predictor’ was ‘Positive Reappraisal. With regard to Anxiety, the same significant ‘predictors’ were found, with the exception of Self-blame, which was not a significant predictor of Anxiety. With regard to Hostility, only Rumination and catastrophizing were significant ‘predictors’.

Multiple regression analysis with the composite scales as ‘predictors’

To study the extent to which symptoms of depression, anxiety, and hostility were predicted by the two composite scales, three other Multiple Regression Analyses (Method: stepwise) were performed with the ‘Total Positively Focused’ scale and the ‘Total Worry Focused’ scales as independent variables (Table 6). Again, all three regression models were significant (p<0.001). Percentages of explained variance were 45%, 34% and 19% for the prediction of Depression, Anxiety, and Hostility scores, respectively. The ‘Total Worry-focused’ scale was a significant and positive predictor in all three outcomes. In addition, the ‘Total Positive- focused’ scale was a significant (negative) predictor only with regard to Depression and Anxiety.

-

Table 6:

Multiple regression analysis composite scales.

Discussion

Aim was to study the associations between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and symptoms of depression, hostility, and anxiety in Bengali adolescents. As a preparatory step the factor structure and psychometric properties of the Bengali version of the Cognitive Emotion regulation Questionnaire (CERQ) were studied. It was the first time that the CERQ was investigated in a developing country.

The findings supported that the CERQ-Bangla had adequate psychometric properties and was a valid instrument to use in a population of Bengali adolescents. On basis of the factor results two composite emotion regulation scales were created (‘Reappraisal-focused’ and ‘Worry-focused’), for which high reliabilities were found. These results corresponded to the results of second order factor analyses in previous studies in which also theoretically less adaptive and theoretically more adaptive subscales were distinguished [4]. Moderate to good alpha reliabilities were found for the specific CERQ scales except for the Other-blame scale, showing that it is valid to use the CERQ subscales in Bangladesh with the exception of the latter scale. This confirmed previous studies in which the validity of the CERQ had been demonstrated in different countries and different languages [9].

The findings also supported the conclusion that more psychopathology was observed in people using maladaptive cognitive strategies like rumination and catastrophizing and less psychopathology was observed in people using more adaptive strategies like positive re-appraisal [3]. More specifically, the results showed that the more a ‘Worry-focused’ cognitive style was used (including rumination, catastrophizing and self-blame), the more Depression, Anxiety, and Hostility symptoms were reported. In addition, a ‘Reappraisal-focused’ style (including Positive reappraisal, Positive refocusing, Planning and Putting into Perspective) was associated with the reporting of less Depression and Anxiety symptoms (but not with Hostility). These results fitted in with the findings of previous studies, where similar relationships were found in various groups (ranging from early adolescents to elderly) [3]. In addition, it shows that the specific strategies predicting psychopathology in a developing country like Bangladesh do not differ from the strategies predicting psychopathologies in economically more developed countries. This underlines the universal importance of cognitive emotion regulation strategies as associated factors of psychopathology.

These results provide suggestions for interventions. They confirm a universal benefit of interventions that focus on changing maladaptive emotion regulation [21]. They show that in a country like Bangladesh – just like in other countries-, targets for prevention and intervention of psychopathology could be found in changing maladaptive cognitive strategies like rumination, catastrophizing, and self-blame into more adaptive strategies like positive reappraisal. Focusing such interventions on adolescents at an early age may reduce the risks of developing psychopathology during adulthood [22], which is important, given the present limitations of mental health services in Bangladesh.

There are some limitations of the study that should be mentioned. First of all, the research was based on cross-sectional data. Therefore, no conclusions can be drawn about causality. Secondly, the results of the present study were based on self-reported data, which may limit the validity of the results. In addition, only eight of the nine subscales of the CERQ could be used because of the low reliability of the subscale Other-blame. Further research should investigate if this reflects a cultural issue or if it has to do with the translation. Although a thorough translation-back-translation method was applied, the meaning of some items could have received a (slightly) different meaning. Future studies should therefore further investigate the translated CERQ-Bangla, replicate this study, use other data-assembly methods like interviews, and include prospective elements.

In conclusion, the present study found indications for relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and psychopathology in adolescents in Bangladesh. This provides possible targets for interventions to improve mental health. However, because this was the first study that focused on such relationships in Bangladesh, further research is necessary. If the results can be confirmed, interventions should be developed to help youngsters change their cognitive styles from worrying to reappraisal.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Prof. Dr. Mohammad Mahmudur Rahman, for his contributions to the translation process.

- Hock RS, Or F, Kolappa K, Burkey MD, Surkan PJ, et al. (2012) A new resolution for global mental health. Lancet 379: 1367-1368. Link: https://goo.gl/tG3Qkw

- Hossain MD, Ahmed HU, Chowdhury WA, Niessen LW, Alam DS (In press) (2004) Mental disorders in Banglades: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 14:216. Link: https://goo.gl/i25HVa

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V (2006) Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: A comparative study of five specific samples. Personality and Individual Differences 40: 1659-1669. Link: https://goo.gl/TkhwAQ

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P (2001) Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences 30: 1311-1327. Link: https://goo.gl/PUFDjD

- Thompson RA (1991) Emotional regulation and emotional development. Educational Psychology Review 3: 269-307. Link: https://goo.gl/xVu7rj

- Thompson RA (1994) Emotional regulation: a theme in search for definition. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 59: 25-52. Link: https://goo.gl/Wa7vtx

- Compas BE, Orosan PG, Grant KE (1993) Adolescent stress and coping: mplications for psychopathology during adolescence. Journal of Adolescence 16: 331–349. Link: https://goo.gl/EUVdK1

- Garnefski N, et al. (2001) De relatie tussen cognitieve copingstrategieeen en symptomen van depressie, angst en suicidaliteit [Relationships between cognitive coping strategies and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and suiciality]. Gedrag en Gezondheid 29: 148-158. Link:

- Domínguez-Sánchez FJ, Lasa-Aristu A, Amor PJ, Holgado-Tello FP (2013) Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire. Assessment 20: 253-261. Link: https://goo.gl/jFFNQV

- Cerutti R, Presaghi F, Manca M, Gratz KL (2012) Deliberate Self-Harm Behavior Among Italian Young Adults: Correlations With Clinical and Nonclinical Dimensions of Personality. Am J Orthopsychiatry 82: 298-308. Link: https://goo.gl/rZKuKq

- Öngen D ( 2010) Cognitive emotion regulation in the prediction of depression and submissive behavior: Gender and grade level differences in Turkish adolescents. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 9: 1516-1523. Link: https://goo.gl/Ey318m

- Tuna E, Bozo O (2012) The Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the Turkish Version. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 34: 564-570. Link: https://goo.gl/9MuET2

- Dadkhah A (2012) Cognitive Emotion Regulation in aged people: Standardization of Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire in Iran. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 10 : 24-27. Link: https://goo.gl/yphLes

- Omran M ( 2011) Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies with depression and anxiety. Open Journal of Psychiatry 1: 106-109. Link: https://goo.gl/T9piDV

- Zhu X, Auerbach RP, Yao S, Abela JRZ, Xiao J, et al. (2008) Psychometric properties of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Chinese version. Cognition and Emotion 22: 288-307. Link: https://goo.gl/LyBpoj

- Jermann F, Van der Linden M, Acremont M, Zermatten A (2006) Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire(CERQ). European Journal of Psychological Assessment 22: 126-131. Link: https://goo.gl/aaJo95

- Loch N, Hiller W, Witthöft M (2011) Der Cognitive emotion regulation Questionnaire, CERQ [The Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire, CERQ]. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie 40: 94-106. Link: https://goo.gl/qrpAuy

- Miklósi M et al (2011) A kognitiv Érzelem-Regulació Kérdőiv magyar változatának pszichometrial jellemzői [Psychometric properties of the Hungarian version of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire]. Psychiatr Hung 26: 102-111.

- Perte A, Miclea M (2011) The Standardization of the Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire on Romanian Population. Cognition, Brain, Behavior. An Interdisciplinary Journal 15: 111-130. Link: https://goo.gl/mVr6WS

- Derogatis L, Cleary P (1977) Confirmation of the dimensional structure of the SCL‐90: A study in construct validation. Journal of clinical psychology 33: 981-989. Link: https://goo.gl/uTDbMF

- Fresco DM, Mennin DS, Heimberg RG, Ritter M (2013) Emotion Regulation Therapy for Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Cogn Behav Pract 20: 282-300. Link: https://goo.gl/RzBjmR

- Wittchen HU, Knappe S, Andersson G, Araya R, Banos Rivera RM, et al. (2014) The need for a behavioural science focus in research on mental health and mental disorders. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 23: 28-40. Link: https://goo.gl/mJjFqb

Table 1:

Factor structure of the Bangla version of the CERQ: items listed by a priori assignment to subscales (without Other-blame).

Items

Factor loadings

I

II

III

Self-blame

I feel that I am the one to blame for it

.39

I feel that I am the one who is responsible for what has happened

.46

I think about the mistakes I have made in this matter

.62

I think that basically the cause must lie within myself

.53

Rumination

I often think about how I feel about what I have experienced

.56

I am preoccupied with what I think and feel about what I have experienced

.65

I want to understand why I feel the way I do about what I have experienced

.52

I dwell upon the feelings the situation has evoked in me

.69

Catastrophizing

I often think that what I have experienced is much worse than what others have experienced

.44

I keep thinking about how terrible it is what I have experienced

.71

I often think that what I have experienced is the worst that can happen to a person

.54

I continually think how horrible the situation has been

.(59)

.29

Positive refocusing

I think of nicer things than what I have experienced

.46

I think of pleasant things that have nothing to do with it

.55

I think of something nice instead of what has happened

.63

I think about pleasant experiences

.71

Refocus on planning

I think of what I can do best

.51

I think about how I can best cope with the situation

.60

I think about how to change the situation

.50

I think about a plan of what I can do best

.69

Positive reappraisal

I think I can learn something from the situation

.42

I think that I can become a stronger person as a result of what has happened

.42

I think that the situation also has its positive sides

.50

I look for the positive sides to the matter

.59

Putting into perspective

I think that it all could have been much worse

.34

I think that other people go through much worse experiences

.38

I think that it hasn’t been too bad compared to other things

.49

I tell myself that there are worse things in life

.57

Acceptance

I think that I have to accept that this has happened

.73

I think that I have to accept the situation

.57

I think that I cannot change anything about it

(.52)

.05

I think that I must learn to live with it

(.39)

.22